- 您現(xiàn)在的位置:買賣IC網(wǎng) > PDF目錄366329 > ACE9030 (Mitel Networks Corporation) Radio Interface and Twin Synthesiser(用于蜂窩式電話的無線電接口電路和雙合成器) PDF資料下載

參數(shù)資料

| 型號: | ACE9030 |

| 廠商: | Mitel Networks Corporation |

| 英文描述: | Radio Interface and Twin Synthesiser(用于蜂窩式電話的無線電接口電路和雙合成器) |

| 中文描述: | 無線接口和雙合成器(用于蜂窩式電話的無線電接口電路和雙合成器) |

| 文件頁數(shù): | 29/39頁 |

| 文件大小: | 379K |

| 代理商: | ACE9030 |

第1頁第2頁第3頁第4頁第5頁第6頁第7頁第8頁第9頁第10頁第11頁第12頁第13頁第14頁第15頁第16頁第17頁第18頁第19頁第20頁第21頁第22頁第23頁第24頁第25頁第26頁第27頁第28頁當(dāng)前第29頁第30頁第31頁第32頁第33頁第34頁第35頁第36頁第37頁第38頁第39頁

ACE9030

29

CHANNEL

NUMBER

1329 or –719

...

2047 or –1

0

1

2

3

...

600

MOBILE TRANSMIT

FREQUENCY (MHz)

872·0125

...

889·9625

889·9875

890·0125

890·0375

890·0625

...

904·9875

MOBILE RECEIVE

FREQUENCY (MHz)

917·0125

...

934·9625

934·9875

935·0125

935·0375

935·0625

...

949·9875

MAIN VCO

(MHz)

962·0125

...

979·9625

979·9875

980·0125

980·0375

980·0625

...

994·9875

An output to drive the phase comparator is generated

from the N1 load signal at the start of each cycle, giving a pulse

every (N1 + N2) counts and to help minimise phase noise in

the complete synthesiser this pulse is re-timed to be closely

synchronised to the FIM/FIMB input. During the N1 down

count the modulus control MODMP is held HIGH to select

prescaler ratio R1 and during the N2 up count it is LOW to

select R2, so the total count from the VCO to comparison

frequency is given by:

N

= N1 x R1 + N2 x R2

but

R2 = R1 + 1

so

N

TOT

= (N1 + N2) x R1 + N2

It can be seen from this equation that to increase the total

division by one (to give the next higher channel in many

systems) the value of N2 must be increased by one but also

that N1 must be decreased by one to keep the term (N1 + N2)

constant. It is normal to keep the value of N2 in the range 1 to

R1 by subtracting R1 whenever the channel incrementing

allows this (i.e. if N2 > R1) and to then add one to N1. These

calculations are different from those for many other synthesis-

ers but are not difficult.

The 12-bit up/down counter has a maximum value for N1

of 4095 and to give time for the function sequencing a

minimum limit of 3 is put on N1. There is no need for such large

values for N2 so its range is limited by the programming logic

to 8 bit numbers, 0 to 255 and to simplify the logic a set value

of 0 will give a count of 256. If a value of 0 for N2 is wanted then

N2 should be set instead to R1 and the value of N1 reduced

by (R1 + 1), also equal to R2.

To ensure consistent operation some care is needed in

the choice of prescaler so that the modulus control loop has

adequate time for all of its propagation delays. In the

synthesiser there is propogation delay T

from the

FIM/FIMB input to the MODMP/MODMN output and in the

prescaler there will be a minimum time T

from the change

in MODMP/MODMN to the next output edge on FIM/FIMB, as

shown in figure 27. For predictable operation the sum

T

+ T

must be less than the period of FIM/FIMB or

otherwise, if the rising and falling edges of MODMP/N are

delayed differently, the prescaler might give the wrong bal-

ance of R1 and R2. This will often set a lower limit on the

frequency of FIM than that set by the ability of the counter to

clock at the FIM rate. For 900 MHz cellular telephones the use

of a

÷

64/65 prescaler normally ensures safe timing.

Fractional-N mode operates by forcing the

MODMP/MODMN outputs to the R2 state for the last count of

the N1 period whenever the Fractional-N accumulator over-

flows, effectively adding one to N2 and subtracting one from

N1, and so increases the total division ratio by one for each

overflow. The effect of this is to increase the average division

ratio by the required fraction.

PROGRAMMING EXAMPLE FOR BOTH SYNTHESISERS

Each channel is 25 kHz wide but as the channel edges are

put onto the whole 25 kHz steps the centre frequencies all

have an odd 12·5 kHz. This is not ideal for the synthesiser but

does give the maximum number of channels in the allocated

band.

The mobile receive channels are a fixed 45 MHz above

the corresponding transmit frequency, as is the case with most

cellular systems. In the ACE9030 the intention is to use the

main synthesiser to generate the receiver local oscillator at the

first I.F. above the mobile receive carrier, and to then mix the

auxiliary synthesiser frequency with this to produce the trans-

mit frequency. A typical I.F. is 45 MHz, leading to an auxiliary

frequency of 90 MHz and a crystal of 14·85 MHz with a tripler

for the second local oscillator, and a final I.F. of 450 kHz.

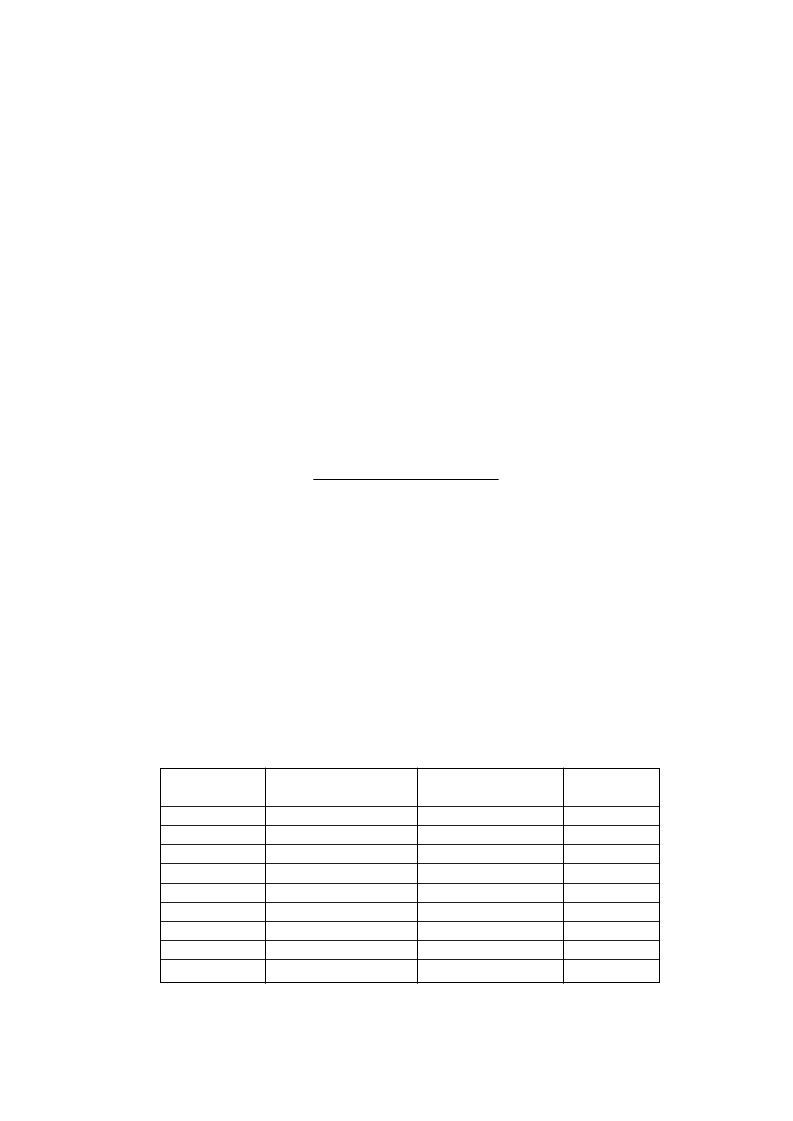

The channel numbers and corresponding frequencies

are shown in table 6.

To illustrate the choice of programming numbers consider

the ETACS system as now used in the UK.

This began as TACS with 600 channels (numbered 1 to

600) from 890 to 905 MHz (mobile transmit) with the provision

to expand by 400 channels (601 to 1000) from 905 to 915 MHz.

This additional spectrum was given over to GSM use before

TACS needed expanding, so TACS was later extended by 720

extra channels from 872 to 890 MHz, to form ETACS and

leaving a somewhat odd channel numbering system. The

channel numbers are stored as 11-bit binary numbers and are

listed here as both negative numbers to follow on downwards

from channel 1 and also as large positive numbers as these

are the preferred names. These two numbering schemes are

really the same, as the MSB of a binary number can be

interpreted as either a sign bit (2’s complement giving the

negative values) or as the bit with the highest weight (1024 for

an 11 bit number, giving the large positive values).

Table 6

相關(guān)PDF資料 |

PDF描述 |

|---|---|

| ACE9030 | Radio Interface and Twin Synthesiser |

| ACE9040 | Audio Processor Advance Information |

| ACE9050 | System Controller and Data Modem(為蜂窩式手機(jī)提供控制和邏輯接口功能的系統(tǒng)控制器和數(shù)據(jù)調(diào)制解調(diào)器) |

| ACE9050 | System Controller and Data Modem Advance Information |

| ACFA-450 | AM CERAMIC FILTERS |

相關(guān)代理商/技術(shù)參數(shù) |

參數(shù)描述 |

|---|---|

| ACE9030IGFP1N | 制造商:未知廠家 制造商全稱:未知廠家 功能描述:Parallel-Input Frequency Synthesizer |

| ACE9030IGFP1R | 制造商:未知廠家 制造商全稱:未知廠家 功能描述:Parallel-Input Frequency Synthesizer |

| ACE9030IGFP2N | 制造商:未知廠家 制造商全稱:未知廠家 功能描述:Parallel-Input Frequency Synthesizer |

| ACE9030IGFP2R | 制造商:未知廠家 制造商全稱:未知廠家 功能描述:Parallel-Input Frequency Synthesizer |

| ACE9030M | 制造商:MITEL 制造商全稱:Mitel Networks Corporation 功能描述:Radio Interface and Twin Synthesiser |

發(fā)布緊急采購,3分鐘左右您將得到回復(fù)。